Artificial intelligence (AI) and IP rights protecting it are becoming more and more economically important. As a technology, AI is becoming equally important as classical software. Legal aspects of AI may take into account those relating to software. Software protection by copyright and software patents can be good starting points. Another important means of protecting AI are trade secrets, which even feature advantages compared to the other legal protections. Here is a summary of the legal situation:

- Patent protection is possible, but the mathematical and logical specifications must bring about physical and technical effects, i.e. the software must be combined with hardware and, in this combination, feature an invention, which has to be "new" (e.g., mere new calculation formulas do not suffice).

- Copyright protection covers software code but does not cover the intellectual-structural conception of the AI system and training of the AI system.

- In many cases, therefore, the most effective protective measure is protecting AI as a trade secret.

- Contracts can effectively support trade secret protection.

Legal protection of innovation in the form of new AI systems

Innovation is often triggered by incentives, such as economic benefits. This is probably the reason why patents have been introduced in Venice as early as the 15th century; the patent system spread throughout Europe thereafter and, by the 18th century, patents enabled legal protection of innovation on a large scale. Today, patents' main properties are still unchanged: Individuals (and other legal entities) can obtain a monopoly on a technical solution. This provides them with a protection for a delimited scope: unlike physical objects which have clearly distinguishable features, patents are outlined by their legal limits and the claims they cover.

This triggers the questions addressed in this article: Innovation is not per se protected by law; rather, distinct rights of so-called "intellectual property" (IP) apply. This wording often induces the misconception of a very broad and comprehensive protection due to the reference to "property" in terms of ownership and legal title. In contrast, however, only individual areas are protected by IP: design (patent) protection, trademark protection, technical patent protection, copyright protection as well as trade secret protection, to name the most important ones. Significant aspects of such IP rights are set out in international agreements, such as, e.g. for patents, the "Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights" (TRIPS) and the European Patent Convention (EPC). The individual legal systems then set out the details of protection. This approach of the law also results in different protection by country; registered rights require to be applied for in every country.

In the following sections, I outline to which extent the individual rights are suitable for protecting AI systems and give a policy outlook as well as recommendation for action to companies.

Patent protection

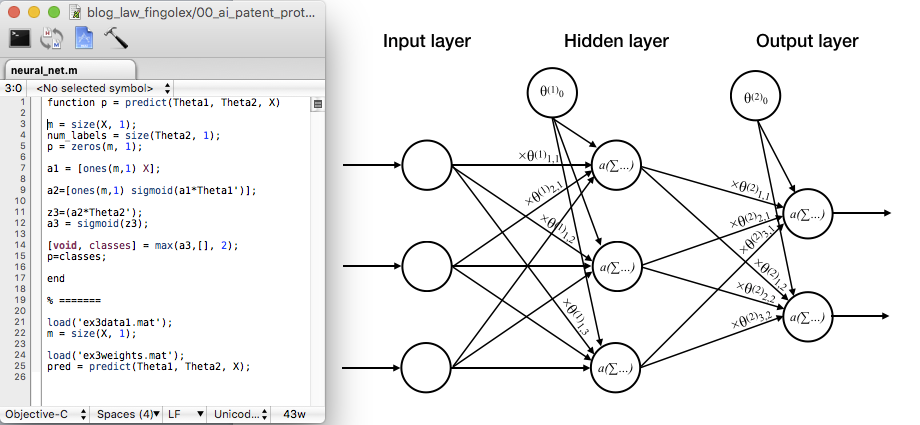

A patent is granted in return for disclosure of technical inventions, insofar as inventions are new, involve an inventive step and are susceptible of industrial application (Article 52 para. 1 European Patent Convention and Sec. 1 para. 1 German Patent Act) and no exclusion applies; for example, scientific theories, mathematical models, frameworks for certain activities (schemes, rules, methods) would be excluded from patent protection (cf. article 52 para. 2 European Patent Convention and sec. 1 para. 3 German Patent Act). At first glance, patent protection for AI systems seems problematic because AI systems are even more abstract than simple software (which is already difficult to be protected).

In contrast to this first appearance, however, in practice, both the European and the United States patent authorities and courts strive to allow patenting of AI systems. While AI systems are not patentable "as such", their specific implementation may be protectable. For a corresponding patent application to be successful, it is necessary that the invention is of a technical nature (refers to a targeted application of forces of nature) and not to be limited to abstract concepts or a mathematical model—the use of concepts and models needs to have a technical effect. Software may be able to fulfil these criteria: although algorithms and models are abstract/mathematical, their application may be technical. Regarding patent protection, the critical decision point is whether the specific technical application of the methods qualifies as an invention. The main question here is whether the invention is both new and technical. In practice, this often proves to be a challenge. Whether this hurdle can be taken in a specific case will usually be key and can only be clarified in collaboration with experts.

While patent protection is granted and needs to be applied for in individual jurisdictions, the applicant has a "grace period" for the application in other countries after filing, the so-called priority period: if a corresponding application is filed in another country within a year, the original filing date applies—the patent thus has priority over other applications made in the meantime (and is deemed to have been made earlier than the other application).

Copyright protection of the training data

Whether a data set, such as a set of training data, is protected under a "database copyright" depends on its design, the procedure of its creation, its structure, the associated routines and their implementation. Subject to certain prerequisites being met, the law protects the investment in these efforts.

Such requirements are often true for training data. In practice though, the more important question is whether an infringement can practically be established. Possible solutions to this challenge may be (fake) marker entries or "virtual watermarks"—scientists have already shown that watermarking is possible for the implementation of machine learning models. We see such a wide range of approaches regarding corresponding training data that we can only provide more detailed suggestions with regard to specific business models.

Copyright protection of the models and their implementation

The actual implementation of the algorithms will regularly be copyrighted as software—this does not hinder anybody from re-implimenting the same algorithm, though. Many authors also doubt that the trained models as such can be protected; the models may fall short of being an intellectual creation. This leads to the conclusion that software protection does not suffice to protect machine learning solutions. Similarly, parameterization of a model will most probably not be covered by database protection—especially since the individual isolated parameters lack usefulness and are therefore not sufficiently independent as required by law.

Copyright therefore only protects a part of the relevant "ingredients" of an AI system, specifically the "programming" of the model by the developer herself/himself and the associated implementation of the algorithms, i.e. the program instructions with which (s)he implements the model and the algorithms. The often bigger effort of training and hence creating parameters for the model is not protected under copyright laws—only the manual adjustments to the program code can be protected.

The abstract descriptions, such as the model or an algorithm, are generally not protected under copyright laws.

Trade secret protection

Protection of trade secrets, on the other hand, is very effective if implemented correctly. It is important that adequate protective measures are implemented on the organizational, on the technical and on the legal side. All three elements are necessary in order for something to enjoy trade secret protection under European laws.

Practically, first identify which core content particularly requires protection; the group of persons having access to that content should be restricted. Install technically meaningful protective measures (authentication and authorization, encryption and other measures). The advantage of these security measures is the direct effect. They help to prevent losing valuable trade secrets even in areas in which you do not want to rely on legal proceedings.

From a legal point of view, all contracts should include provisions on permitted/permissible use and restrictions, e.g., on reverse engineering and automated readout. Although contractual provisions cannot prevent a technical readout from taking place, e.g. by means of an API (which, according to current knowledge, appears to be quite possible), they do help to take legal action against the person reading out.

Protection of work results created by AI systems

Again and again, a discussion arises on whether the results of AI are protectable or not. Such results may be of great commercial value—consider, for example, an algorithm creating the new summer hit after analyzing large numbers of songs and listening habits. The law takes a pragmatic view on this: only legal entities can acquire intellectual property rights, and neither computers nor AI systems are legal entities. Whether the operator of the system can obtain rights to the results depends on whether the system is the operator's tool, with the operator consequently coming up with his own intellectual creation (similar to the piano on which the composer plays during his creative process and similar to the camera the photographer uses to create the next photographic work) or whether the system creates works autonomously—in the latter case protection would fail because no creator exists from a legal perspective.

You might draw a parallel to the well-known monkey selfies: courts have discussed a case of a photographer who gave his camera to a monkey which in turn took a selfie. The courts held that the photographer has no protective rights to the selfie as he had not created it himself. The selfie is therefore "public domain" (in the Anglo-Saxon sense of the word), i.e. it is a purely public good: being an animal and not a human, the monkey cannot assert any intellectual property rights (just as the monkey cannot acquire physical property according to our understanding of the law). The law therefore treats computer intelligence in the same way as natural intelligence—albeit not as human intelligence.

Legal policy outlook

The patent authorities (in particular the European Patent Office and the United States Patent and Trademark Office) are visibly open to the patentability of software-based systems, implying or even explicitly including AI systems. Practically, however, different hurdles need to be overcome.

Particularly for smaller companies, in view of their financial resources available, it is questionable whether patent protection is feasible at all, or whether other means of protection should be focused on. Given the fact that particularly smaller companies are among the most innovative and that the costs of examining the patent situation (including Freedom to Operate—FTO) can be significant, policymakers should consider intensively whether the presumably innovation-promoting patent system really promotes innovation. The protection cycles of patents and copyrights have already become very long compared to the innovation cycle (especially in the IT world); they outlast several product cycles—hence, it should also be examined whether this duration of protection should be reduced.

Exclusive rights to patent-generated inventions would appear to make sense if AI systems were given their own legal personality. However, this is neither currently the case, nor is an acute need to adapt the system given. This applies all the more since the legal system features a consistent mode of protecting intellectual property rights: all relevant property rights require an intellectual creation (which usually is: creativity)—but today's AI systems are not in a position to do so. On the other hand, the results can already enjoy protection as trade secrets if appropriate measures are taken.

Recommended action

In order to determine which mechanisms provide particularly well suited to protect for a certain (AI) development, several considerations need to be made:

- Should the AI system or its output be protected?

- What is the value of the technology (financial and competitive)?

- In which part of the technology is the innovation, in which a big investment (which are specifically valuable and unique)?

- How difficult is a "plagiarism of the solution"? Which parts are simple, which are difficult and where are the technical challenges?

- Which parts would have to be disclosed to describe a patent claim (in simple terms: what is the new technical solution—it has to be described in a comprehensible way)?

- Are there any peculiarities regarding the individual elements of the system (model structure, training algorithm, training data, trained model, application algorithm) in relation to the previous questions?

- What are the relevant markets and expected shares in the company's sales (ideally also possible sales revenues)?

- Who comes into direct contact with the technological solution?

This assessment helps determine the protection path, such as whether patent protection should be protected, whether protection should be sought under copyright law, or whether the solution's nature as a trade secret should be supported, relying on the associated legal protection under trade secret laws.

Irrespective of the outcome of this evaluation, in most cases, it is advisable contractually secure the interfaces and thus limit the use to certain legitimate purposes to make analysis of the technology more difficult. Even if, for example, a patent is sought and obtained, this usually only covers part of the solution and the remaining parts can also be protected in their value to a certain extent by treating them as trade secrets.

Evaluation tool and legal consulting

I offer a simplified tool for this in the form of pre-evaluation form for download here; this should, however, only be used as a preparatory work for a discussion with experts (patent attorneys and/or attorneys-at-law).

Download evaluation tool (currently only available in German): Bewertungsübersicht

I, attorney-at-law Baltasar Cevc, would be pleased to assist you in assessing which legal instruments are most appropriate for protection and in formulating and negotiating the relevant contractual provisions.

Note

Attorney-at-law Baltasar Cevc is one of the two authors of the article "Patentschutz für Systeme Künstlicher Intelligenz?" (translates to: Patent protection of Artificial Intelligence systems?), published in the Intellectual Property Journal/Zeitschrift für Geistiges Eigentum, 2019, 137-169 (Volume 2, Volume 11). This article builds on certain content from this article and presents business aspects in core aspects, but the presentation here is oriented towards the business perspective and does not reflect the legal considerations in the article extensively. Furthermore, parts of this article are completely independent of the article mentioned.

The presentation cannot replace any legal advice in individual cases, it serves only the first rough orientation.